May 18, 2022 — Haukur Skúlason

How much am I paying for using my money?

Most of us use debit or credit cards to pay for products and services in our daily lives. Those cards are most likely issued by our bank, whether it is the good old plastic card or a smart phone version such as Apple Pay. What I would like to know is just how much it costs me, at the end of the day, to use a card to pay for every day things, such as food, entertainment and travel. In other words, how much am I charged for using my money?

To be fair, most of us probably do not know what this cost is, although we have a feeling that the banks charge us all kinds of hefty fees. We all have different ways of using bank accounts and cards, some of us use debit cards exclusively as well as our salary account, some of us primarily use credit cards and then settle them at the end of the month, while others might use a mix of these, or even exclusively cash.

The Central Bank of Iceland gathers all kinds of information about card usage and Icelandic bank accounts and there we have a wealth of data1. Looking at the numbers we see that over the course of the last 12 months, Icelandic households have bought goods and services, using debit cards, for ISK 490 billion, and of those around ISK 65 billion were spent abroad (including foreign online purchases). In the same period, Icelandic households spent ISK 570 billion using credit cards, thereof ISK 100 billion abroad. The total spending of Icelandic households for the last year was thus around ISK 1.100 billion.

At the end of March 2022, Icelandic households had, combined, around ISK 225 billion on their current accounts (usually linked to debit cards), and additionally almost ISK 450 billion in savings accounts that offered withdrawal without notice, based on the same Central bank data.

These figures are so large that most of us can hardly comprehend them, and therefore it is helpful to look at them as an average for every person in Iceland 18 years or older (keep in mind that averages are one thing, the distribution is another matter entirely, but we lack the data for that). We see that the “typical, average” Icelander has around ISK 770.000 on his current account at the end of the month. Lindsay, a hypothetical Icelander, represents this “typical, average” person - the data portrayed by the Central bank. Most of us will find ourselves with a higher or lower amount on our account, we might use our cards more frequently or more seldom, but the averages are there nonetheless. Lindsay is thus a perfect average, typical person in this respect.

Icelandic banks charge fees for card usage as per their pricing schedule, but for the sake of simplicity, let's assume that Lindsay pays an annual fee, transaction fees and sometimes buys products online from foreign stores (such as Boozt or Amazon), as the Central bank data suggests.

The banks offer all kinds of cards with different features, as one might expect, and (again) for the case of simplicity let's assume that Lindsay has a card the banks usually refer to as a “gold” card, that is not the cheapest option and not the most expensive one.

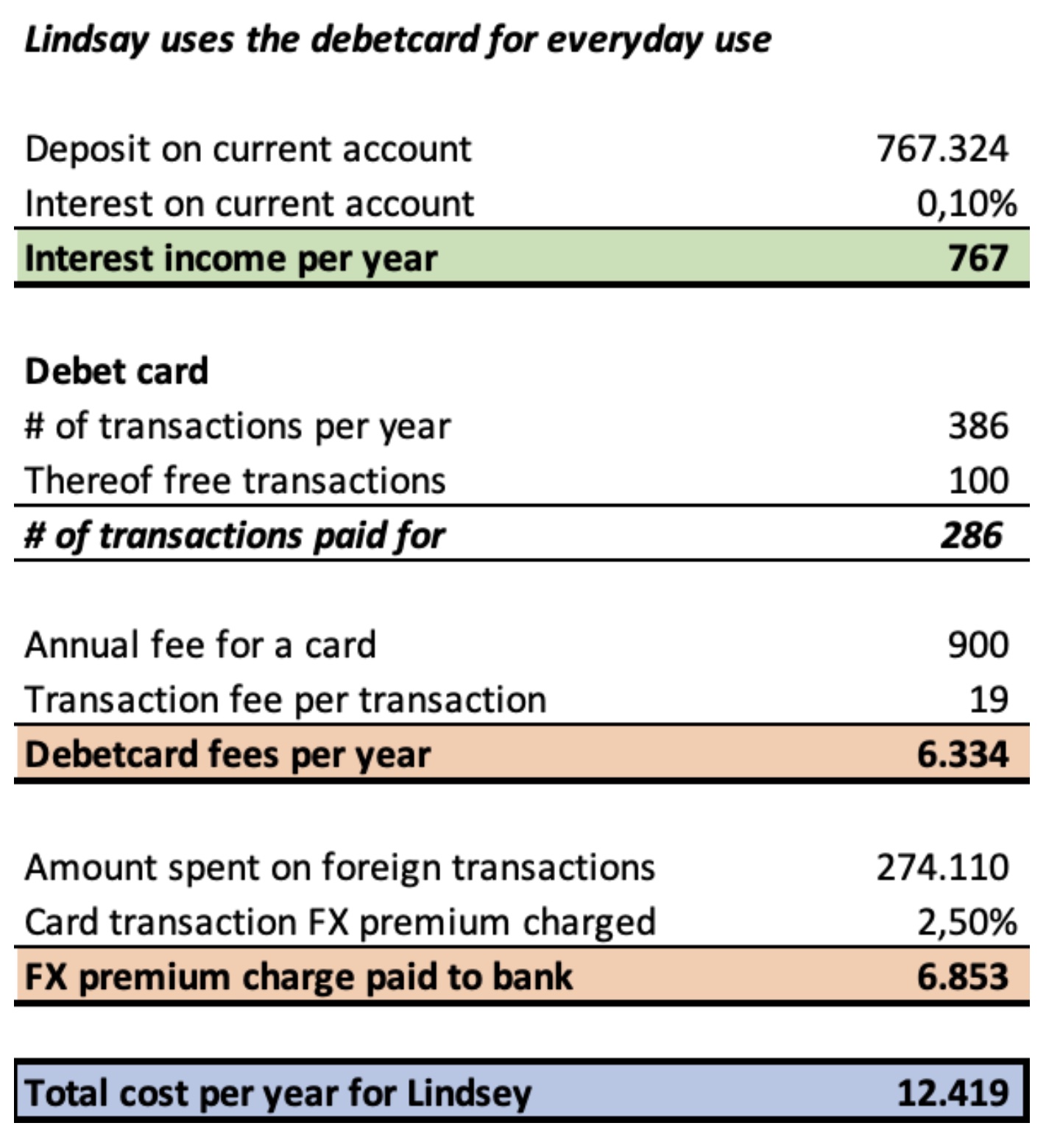

If Lindsay uses the card for daily consumption and has the average amount on the current account, that amount accrues interest, but at the same time Lindsay has to pay all kinds of fees and even hidden chargers, so in the end the cost for Lindsay is around ISK 12.500 per year. Lindsay pays more than one thousand krónur per month for accessing the money and using the card.

What Lindsay does not easily see is the transaction cost and annual fee to be paid. Those are around ISK 6.300 per year and in addition to that, Lindsay pays almost ISK 7.000 per year in for a worse exchange rate than normal.

In this case, it makes no difference whether Lindsay uses a plastic card, Apple Pay or pays online - all transactions are transactions in the same sense.

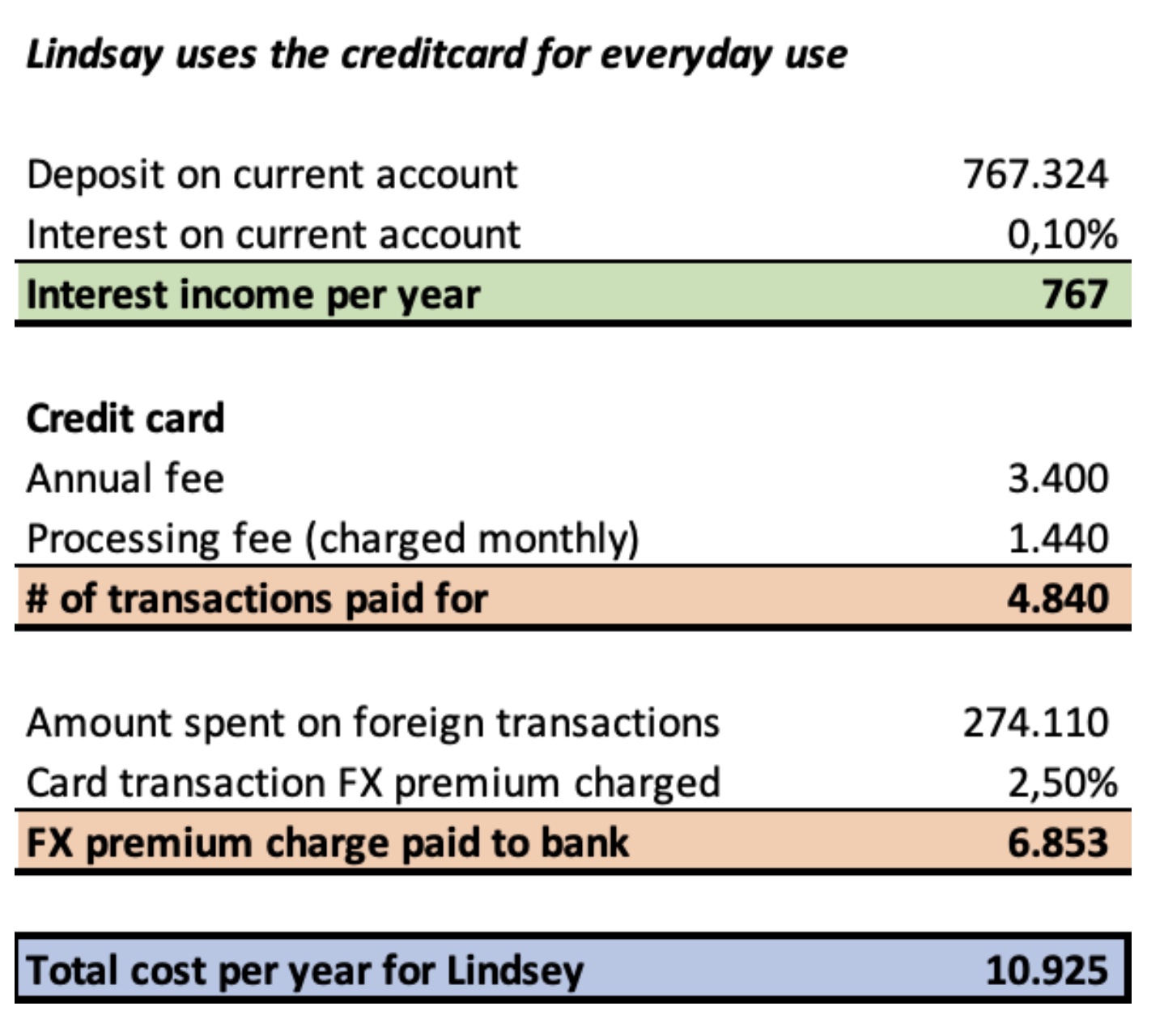

Let us further assume that Lindsay uses a credit card rather than a debit card, to avoid those pesky transaction fees because those are not charged from credit card transactions. Assuming the consumption is completely the same, we see that Lindsay has very similar costs, despite no transaction fees - they have been replaced by cryptic processing fees charged for showing Lindsay a summary of the monthly transactions on the computer.

The annual fee for a credit card can be significantly higher than the shown example (tens of thousands of krónur per year even), but to be fair, there are also many perks associated with those cards such as insurance, discounts and more. While the processing fee has replaced the transaction fee, the FX premium has not changed.

Lindsay has, despite all this, saved around ISK 1.500 krónur per year and the cost of having a credit card and current account is around ISK 11.000 krónur per year instead of ISK 12.500 krónur per year using the debit card.

Some readers might have a “system” in place to get around these costs, such as moving money around different accounts to find the higher rates, using cash to a significant degree etc. But the question remains, why should I be paying all these fees just for being able to use my own money? It is, after all, my money! And why do I have to go through all kinds of exercises every month to reduce this cost? Why can't the bank just give me a fair deal?

Now let's assume that there are 290 thousand Icelanders just like Lindsay. Those people pay, collectively, around ISK 3,5-4,0 billion per year, just to be able to access their salaries to buy everyday things. I assume that Icelandic ouseholds could do quite a lot with that kind of money.