May 17, 2022 — Haukur Skúlason

Why are the interest rates on my salary account so low?

Most of us have bank accounts, whether they are so-called “current accounts” linked to our debet cards and, sometimes, overdraft, or savings accounts.

The interest rates the banks pay us usually don’t get as much attention as the interest rates we have to pay the banks. When we put our money into a salary account, or a savings account, we are effectively lending the bank our money, and the banks should of course pay us fair and normal rates for those loans, just as they expect us to pay them fair and normal interest rates on the loans they have extended to us.

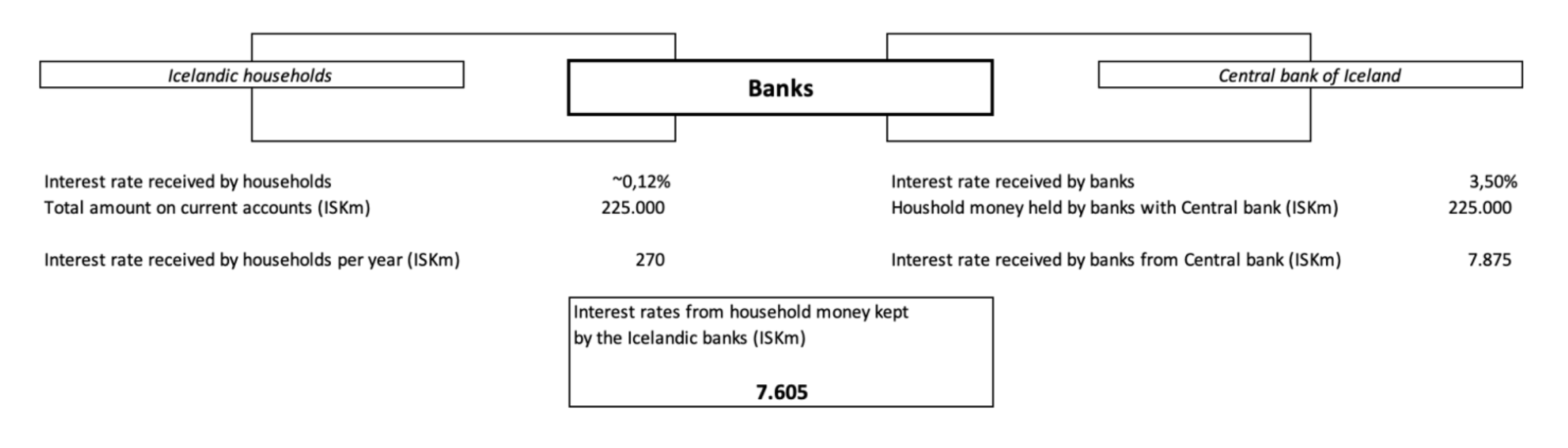

The Central bank of Iceland has a lot of data about the Icelandic banks, and there we can see that Icelandic households have around SK 225 billion, collectively, on the current accounts with the local banks1. That means that if households were just a single customer of a bank, that person would have ISK 225 billion on its debet card at the end of each month. The rates the banks pay on that deposit ranges from 0,05% - 0,20% per year, according to the price schedules of the banks.

The banks have to do something with this money, and if we look at how much money the banks, themselves, lend to the Central bank (they basically deposit money at the Central bank just as we deposit money with our bank), that amount is around ISK 235 billion2.

We can generalize a bit and state that the money Icelandic households keep on their current accounts is, by and large, immediately placed by the banks into their own accounts with the Central bank (the figures suggest this, and also the nature of these types of bank accounts from a bank-ish perspective). The banks thus keep our spending money at the Central bank, on their own bank accounts there.

The Central bank offers two types of bank accounts to banks, a current account and a “savings account” where the funds are “locked in” for a week at a time. The Central bank then pays the banks a specific interest rate on those deposits, as it should. The rates the Central bank pays for money on its savings account is called the Main rate, and is currently at 3,75%, and pays 3,50% on its current account offered to the banks.

What the picture above shows us is that Icelandic households place ISK 225 billion with the Icelandic banks, who in turn place the same billions with the Central bank in their own name. The banks get paid just shy of ISK 7,9 billion in interest per year on those deposits, but pay the households only ISK 270 million in interest. In other words, the banks pocket 97% of the interest rates they receive on the spending money of households, and give the owner of the money, us, 3% of the interest.

Based on the above, we can state that the only thing the banks do with our spending money is to move it to the Central bank, where it sits risk free until we need to use it. Money on current accounts is notoriously tricky to use for lending to bank customers, for that more “sticky” funding is needed such as term deposits (or deposits that are locked in for weeks, months or years), equity, bonds and such. Our deposits are effectively kept at the Central bank, but we only get a small fraction of the interests they receive.

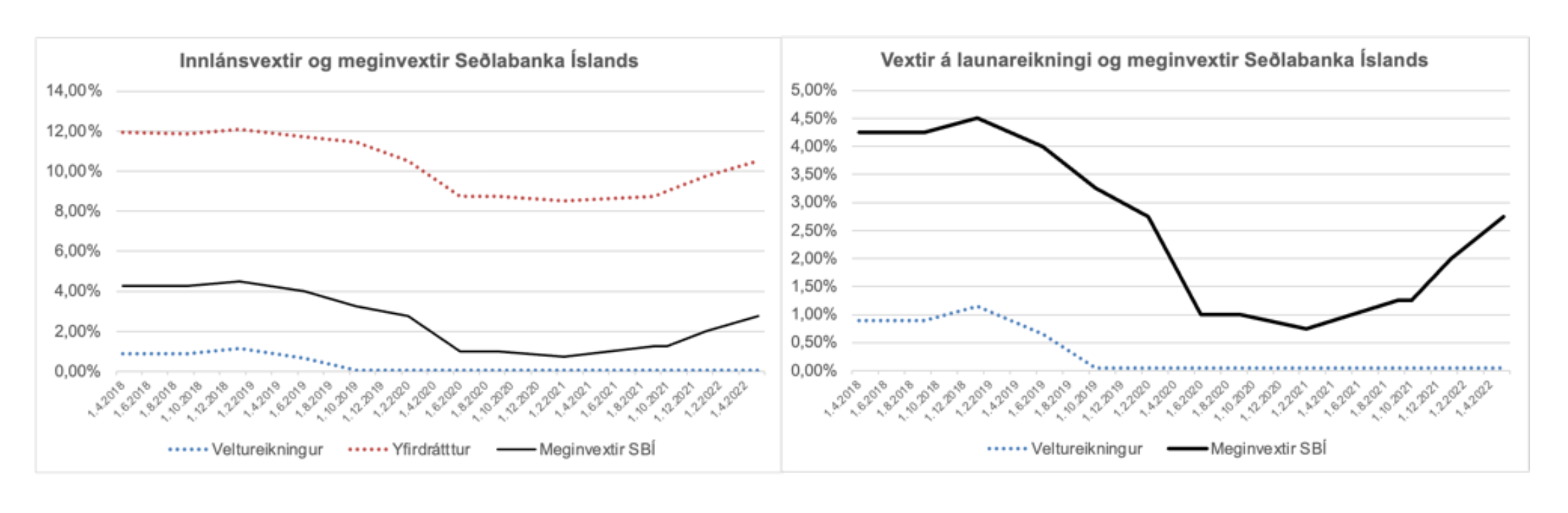

If we look back a few years and investigate how interest rates have gone up and down, we see that the banks are very efficient in raising their lending rates when the Central bank changes its own rates (and to be fair, they lower them efficiently as well when the Central bank is lowering its rates). Below, to the left, we see that typical overdraft rates from the beginning of 2018 to the end of April 2022, in addition to the Central bank Main rate and typical interest rates on a household current account.

When the Central bank started to lower its rates in the beginning of 2019, interest rates on both overdrafts and current accounts available to households went down, and indeed the rates on current accounts went almost down to 0%, ranging from 0%-0,1%. When the Central bank started to raise its rates again in the middle of 2021, overdraft rates went up at the same time (it became more expensive for households to borrow, not just an overdraft but all types of loans), the rates on the current accounts moved next to nothing, if at all.

The above right image shows a “zoom in” of the left image, with only the Central bank main rates and the typical current account rate available to households. Households have not seen an increase in their current account rates since the middle of 2019 despite the Central bank having raised its rate considerably since then.

This raises a few questions. Firstly, why don’t Icelandic households get a much higher rate on their money held in current accounts with the banks, since the money is, after all, held at the Central bank in the name of the banks? If our money carries 3,75% interest, or thereabouts, when it is at the Central bank, why don’t we get much higher rates when the money is at our bank? The bank can’t use this money for much else anyway than keep it with the Central bank.

Secondly, why don’t the rates on my current account change then the Central bank raises its rates? When the Central bank changes its rates, is it normal that the banks raise the rates on our loans almost simultaneously, but little or nothing happens to our savings rates?

Of course it should be normal for banks and their customers to split the interest rates received by the Central bank, but it cannot be normal that the split is 97 to 3 in favor of the banks.

Let us assume that the split was, instead, 50 / 50, that is to say the banks kept 50% of the interests the Central bank pays, and the households 50%. That would mean that, with the current Main rate at the Central bank, Icelandic households would have just over ISK 3,5 billion more to spend per year than they currently do.